The legal and economic foundations of share structures in the US - particularly in Delaware - differ fundamentally from those of many other countries, especially European ones, where corporations are often required to demonstrate a substantial minimum capital contribution upon incorporation, pay it in fully, or formally contribute assets. This traditional understanding regularly leads to misunderstandings among founders and investors when they first encounter US corporate law.

This is because the US operates on a completely different, much more flexible model: Par values (nominal values) are purely technical figures. They bear little relation to actual contributions, the true value of the company, or the subsequent stock price. This very difference - especially in international reverse mergers and capital measures - repeatedly leads to incorrect assumptions.

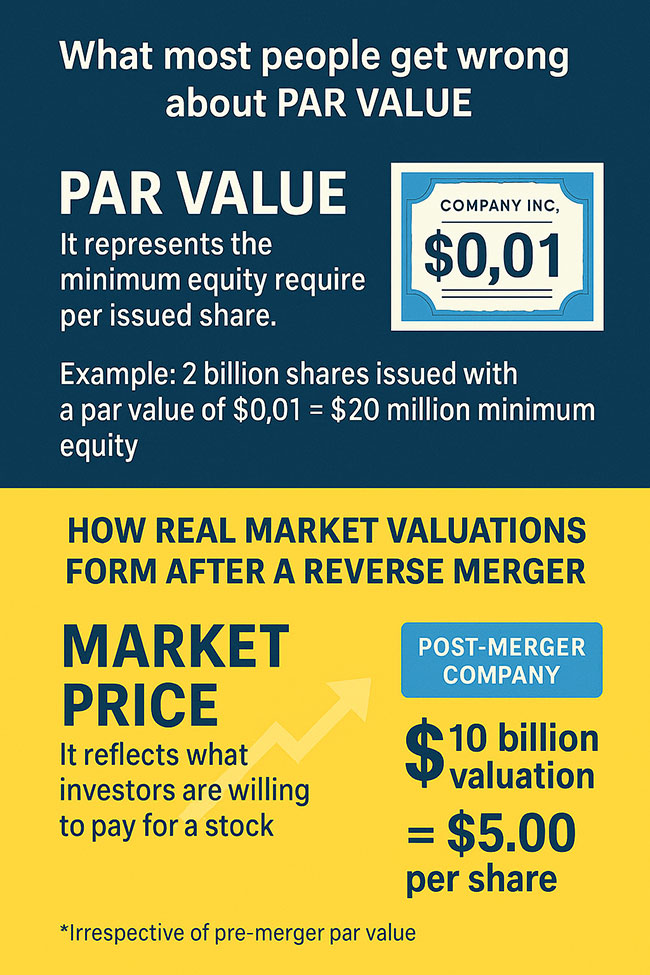

To dispel these typical misunderstandings, here is a clear, practical, and easily understandable explanation of the US system: how nominal values work, how market prices are determined, and why American share structures often operate with extremely low par values.

Here is the simple truth, hardly known outside the US:

A company must "have the nominal value for every share."

That sounds logical – but it's completely wrong.

- Par Value has almost nothing to do with the real company value

In the U.S. - especially Delaware - par value is only a legal minimum per share for bookkeeping.

It does not determine:

- how much capital the company needs

- how much a shareholder must pay

- or what the stock will trade for

Example:

- 2,000,000,000 authorized shares

- Par value = $0.01

Many assume:

“Then the company must have $20 million in equity.”

False.

Only issued shares create “stated capital.”*)

And even then, the board determines the fair value of the consideration.

*) “Stated capital” is the legally recorded capital amount assigned to an issued share under U.S. corporate law.

It equals at least the par value of the share, but can be higher if the company chooses to designate more.

Key points:

- Stated Capital is not the market price.

- It is not the real paid-in capital per share.

- It is a minimum legal equity amount, recorded for creditor-protection and corporate accounting purposes.

Example:

Par Value = $0.01

One share is issued → at least $0.01 is booked as “Stated Capital.”

In short:

Stated Capital = the legally required minimum equity assigned per issued share—regardless of actual valuation or trading price.

- While it is possible to issue shares in exchange for intangible assets as follows, this is not necessary

Delaware allows issuing shares in exchange for:

- software

- blockchain infrastructure

- web platform

- domain names

- algorithms

- proprietary code

- intellectual property

- even services

The board passes a resolution setting the fair value.

Result:

Millions in “additional paid-in capital” with zero cash deposited.

- Why do companies pick extremely low par values (0.01 / 0.001 / 0.0001)?

Because high par values:

- inflate stated capital unnecessarily

- increase franchise taxes

- complicate future equity rounds

- hinder uplisting policies

This is why almost all U.S. tech firms use ultra-low par values.

- So how is the stock price determined AFTER the reverse merger?

Very simple:

The market determines the stock price based on:

- perceived future growth

- investor demand

- analyst expectations

- the business model

- industry comparables

- IR work and storytelling

Example:

If the market values the post-merger company at $10 billion, and there are 2 billion shares outstanding:

Implied stock price = $10,000,000,000 ÷ 2,000,000,000 = $5.00

This has nothing to do with par value.

- Why this matters for reverse mergers

Because it allows you to:

- achieve large valuations

- maintain a big authorized share pool

- structure investor 10× ROI packages

- integrate shells efficiently

- satisfy institutional requirements

Par value is a legal formality.

Market value is determined after the merger, by investors — not by the incorporation documents.

Conclusion

Par value ≠ company value.

Par value ≠ stock price.

The real price forms in the market, driven by expectation, demand, and narrative.

This is exactly why well-structured reverse mergers can produce exponential investor returns in months.

In more detail and in the context of a reverse merger:

Why Is the Par Value Only $0.01 When the Stock Trades at $5.00?

Because par value (nominal value):

➡️ is only a legal/technical number

➡️ is not the real economic value of a share

➡️ is not the trading price at the stock exchange

➡️ is often extremely low (0.0001 – 0.01 USD)

➡️ is chosen freely by the company

The market value is something completely different:

➡️ It is defined by supply & demand

➡️ It reflects the valuation investors expect

➡️ Higher company valuation → higher per-share price

Example: Why Set Par Value at $0.01?

A company defines:

- Par Value: $0.01

- Authorized/issued shares: 2,000,000,000 (2 billion)

What happens?

✔ Par value only serves as the minimum legal capital value per share

This means:

The company must show at least $0.01 in equity for each issued share.

But:

🟦 Par value is NOT the IPO price and NOT the stock market price.

Then the valuation determines the real price.

If the company is valued at $10 billion with 2 billion shares:

👉 The market creates the $5.00 price — not the par value.

Even if the par value were $0.0001, the share could still trade at $5.00.

Why Not Set Par Value = $5.00 From the Start?

Because legally and financially it would be a disaster.

If par value were $5.00:

The company would need to show $5.00 of paid-in capital per share.

For 2 billion shares, that means:

→ The company would be forced to contribute $10 BILLION in real capital.

→ Completely unrealistic.

→ Makes the capital structure rigid and unusable.

→ Highly unusual in U.S. corporate practice.

Delaware, Nevada, Wyoming strongly recommend ultra-low par values, which is why nearly all U.S. corporations use:

- $0.00001

- $0.0001

- $0.001

- $0.01

Why Ultra-Low Par Values Matter

- Minimal capital requirements for founders

You can issue millions or billions of shares without needing huge cash deposits. - Maximum flexibility for future capital actions

Splits, reverse splits, additional issuances become simple. - Preferred by U.S. regulators

The SEC expects low par values for tech, SPAC, and IPO structures. - International investors understand this standard

It is the norm in nearly every U.S. tech IPO.

Core Idea — in one sentence

Par value is only a legal minimum and has nothing to do with the real stock price — which is determined entirely by market valuation (e.g., $5.00), regardless of whether the par value is $0.01 or $0.0001.